(1649 words) [1]

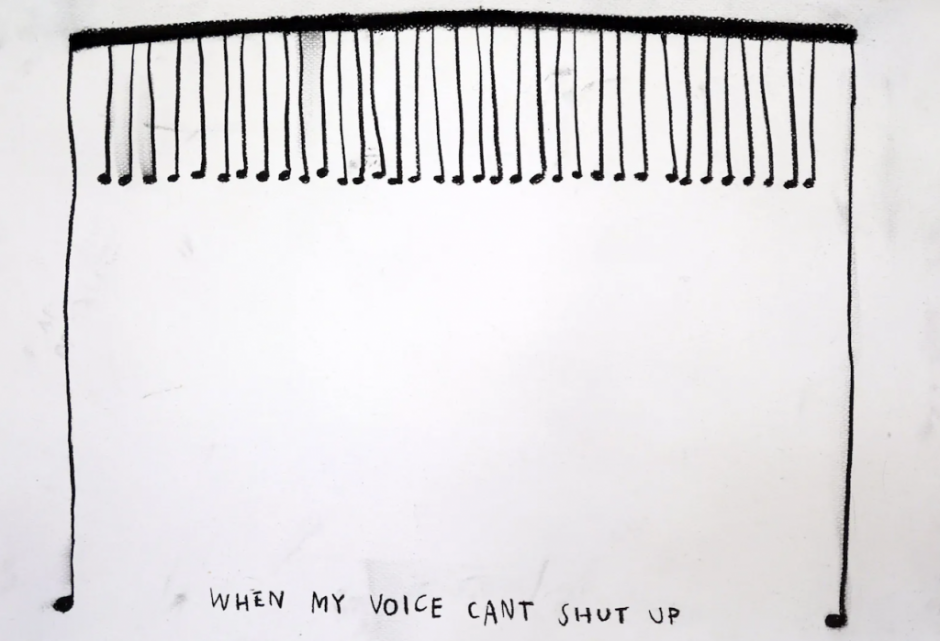

For the fifth week in a row, my student sent me a last-minute excuse for why he couldn’t come to college. Every week, he emailed me or texted me at the last minute, tummy issues, headaches, and transport problems. By that point, they had missed all the initial sessions to meet their tutor group, me and their writing tutor, the year meetings, lectures, and all the parallel optional sessions we offer to students. After several attempts, we started a conversation texting via Teams. Because they found it so hard to communicate in English, they suffered from massive anxiety and couldn’t bear coming to college.

My proposal addresses a specific language barrier affecting some of our Chinese BAFA Y3 students. Over the year, my student and I tried many different strategies—first, one-on-one sessions on Teams, followed by one-on-one sessions in person. Once we developed enough access intimacy, and trust, we started using Google Translate on my phone, which allowed for a sustainable rhythm in our conversations. (Mingus, 2011) I would speak on my phone, and he would read the translated text in Chinese. He would then speak in Chinese on his phone, and I would read what he said.

I am a tutor group leader and 0.8 Y3 member of staff in the BA Fine Arts at the Chelsea College of Fine Arts. We have a large Y3 cohort, with 163 students clustered in Tutor Groups of ten or eleven students. I’m responsible for three of those groups as well as general sessions and administrative tasks. My tutor responsibilities include coordinating with writing tutors, facilitating one-on-one and group sessions focused on the students’ art practice, and providing pastoral care. Just under half of our students are international, which means that pedagogically integrating such a significant cohort has a massive impact on the learning environment. Although UAL Attainment Profiles do not cover Asian international students, we are very aware of the barriers and lack of institutional support these students encounter on a day-to-day basis. (Internal Access Monitoring, no date).

We identified a handful of students experiencing similar issues with English language access. This was confirmed by other tutors in the year and across the course in general. It was noted that team members had identified this cohort since Foundation as having lower IELTS grades for admission due to recruitment goals. It’s challenging to verify this information, but the Language Centre’s survey on English language proficiency levels of international students, carried out this year, suggests that this is a broader issue at UAL.[2] We scheduled support sessions with a staff member who spoke Mandarin. This intervention was very successful.[3] It had full attendance by students who hadn’t been present in the course, and the students were incredibly chatty, happy, and relaxed. However, we didn’t have a budget to pay for extra HPL hours to continue those sessions or resources that would allow this member of staff to support them throughout the year.

By the time we reached my final group sessions of the year, which were smaller than the regular tutor group, we passed my phone around, and a student or I would read the English translation to the group. Over the year, my student’s mood and engagement with the course markedly increased; his writing and practice-based work improved considerably, and his marks improved by almost two bands from the previous year. Y3 requires a significant amount of writing, reading, and critical analysis, making it a very discursive program. A language barrier becomes incredibly prejudicial at this point. This is one of the reasons why most of the students who are diagnosed with Dyslexia or ADHD are only flagged and referred to Disability Services this year. Although these methods worked quite successfully in the end, “Academic life [..] at every university, is inherently social”. (Jack, 2019, p. 86) This method failed to address all the larger sessions, and it created a parity issue with my other tutor groups since our sessions were much slower.

My proposed intervention is to expand on the methods I developed with my student so that (1) I’m better prepared next time and can intervene faster and more effectively, (2) I can share it with colleagues, (3) I can have a solution better fitted for group discussions and crits that HPL and guests can quickly implement and (4) it can also be used in larger sessions like lectures and year meetings.

My proposed intervention involves collaborating with the Digital Support Team and the Language Support Team to develop a live captioning method utilising the technology and techniques developed during the COVID-19 pandemic to facilitate digital access. A few years ago, I attended a series of Digital Access trainings that included the use of Microsoft Teams live captioning translation features. These allow live captioning to be set for a meeting, with the option to enable live translation to a different language locally. This would mean that my student could have joined any group sessions from the beginning and followed the live, translated captions on his laptop. Ideally, we would find a solution that allows him to speak in Chinese on his Teams, and I or one of the other students could read the translation out loud. This will require additional tools, such as clip-on mics for improved clarity, which are available from the AV Team for lectures and larger sessions and can be booked from the Loan Store. I’ve contacted the Digital Support team to discuss potential alternatives, as the live captioning translation for Teams is now only available in the Premium version.

Image credit: https://www.knowledgewave.com/blog/live-translated-captions-in-microsoft-teams-meetings

This intervention would expand our access support for d/Deaf access.(“Friends & Strangers”, 2023) I’ve worked with supporting subtitling and closed captioning in a previous role and use some of those resources, such as audio description writing techniques, as part of writing pedagogical tools in the course. Through that period and my own experience as a non-native English speaker with a chronic illness that involves bouts of fatigue, I have come to understand that captioning, like most access infrastructure, can expand modes of engagement for a much larger population than the one it is initially aimed at.

As my PGCert tutor has pointed out, this intervention extends beyond my professional remit. As lecturers’ free support hours have been reduced over the years, these problems are likely to become more frequent. But I’m also a firm believer that the most effective interventions are always led on the ground and by the staff who are in direct contact with students. (Cussiánovich Villarán and Schmalenbach, 2015)

The efficacy of this intervention could be evaluated using both qualitative and quantitative methods, such as recording direct observations of engagement through attendance at sessions, workshops, and year meetings. It would also be possible, as we did this year, to routinely check with staff on the effect on their tutor groups. It will also be important to check with other students in the tutor group and attendance at open sessions. Part of the goal is to avoid alienating Chinese students by making them hyper-visible. Quantitative data can be collected through attendance and by mapping grades at the end of Year 3, as well as comparing them with the grades from Year 2. We already do this every year to identify biases in our teaching.

“Peruvians don’t make art. Peruvians don’t make theory.” For about a year and a half, my Latin American Studies PhD supervisor would find a way to convey this to me, the Peruvian PhD student.[4] As I mentioned in my blog post on race, having been a racialised English-language learner international student, I have a profound sense of political solidarity with the barriers and prejudices those students face. (Francke, 2025) There is a profound sense of dehumanisation in ignoring the language barriers that UAL itself has produced.[5] The lack of concern for the barriers those students face relates to how the college perceives them as consumers “buying” a degree, rather than active participants in a pedagogical environment. Low expectations are set up institutionally and repeated in larger political and social discourses that are being amplified in the media and becoming pillars of current fascist government trends, such as vilifying international student visas in the UK and the US.(Bradbury, 2020; Kiely, 2025; Moynihan, 2025) It is fundamental to me that, as an art course, we nurture an environment of epistemic abundance and create the conditions to learn together from everything that all of us bring to the course. It is by modelling treating every student as a full human that we can help our students develop as people and as artists.

Bibliography

Bradbury, A. (2020) ‘A critical race theory framework for education policy analysis: the case of bilingual learners and assessment policy in England’, Race Ethnicity and Education, 23(2), pp. 241–260. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2019.1599338.

Brixton Black Women’S Group (2023) Speak Out!: The Brixton Black Women’s Group. Verso Books.

Bryan, B., Dadzie, S. and Scafe, S. (2018) The Heart of the Race: Black Women’s Lives in Britain. Verso Books.

Chicano! History of the Mexican-American Civil Rights Movement (1996). NLCC Educational Media.

Cussiánovich Villarán, A. and Schmalenbach, C. (2015) ‘La Pedagogía de la Ternura -Una lucha por la dignidad y la vida desde la acción educativa | The Pedagogy of Tenderness –A struggle for dignity and life from the educational action’, Diá-logos, 16, pp. 63–76.

Francke, A. (2025) ‘Unit 2 – Blog Task 3: Race’, 22 June. Available at: https://andreafranckepgcert.myblog.arts.ac.uk/2025/06/22/unit-2-blog-task-3-race/ (Accessed: 1 July 2025).

“Friends & Strangers” (2023). (Art21). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2NpRaEDlLsI (Accessed: 5 May 2025).

Garrett, R. (2025) ‘Racism shapes careers: career trajectories and imagined futures of racialised minority PhDs in UK higher education’, Globalisation, Societies and Education, 23(3), pp. 683–697. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2024.2307886.

Gibson, J. (2025) ‘English Language Levels Survey – follow up’.

Internal Access Monitoring (no date). Available at: https://dashboards.arts.ac.uk/dashboard/ActiveDashboards/DashboardPage.aspx?dashboardid=c977e2c6-878b-48df-b8e7-aa2c5fe6a3fe&dashcontextid=637396550877188156&resetFilt=true (Accessed: 1 July 2025).

Jack, A.A. (2019) The Privileged Poor: How Elite Colleges Are Failing Disadvantaged Students. Harvard University Press.

Kiely, E. (2025) ‘Ed Kiely · Short Cuts: University Finances’, London Review of Books, 23 May. Available at: https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v47/n10/ed-kiely/short-cuts (Accessed: 25 June 2025).

Mingus, M. (2011) ‘Access Intimacy: The Missing Link’, Leaving Evidence, 5 May. Available at: https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2011/05/05/access-intimacy-the-missing-link/ (Accessed: 19 February 2024).

Moynihan, D. (2025) ‘The Attack on International Students’, Can We Still Govern?, 13 April. Available at: https://donmoynihan.substack.com/p/the-attack-on-international-students (Accessed: 25 June 2025).

Neill, A.S. (1990) Summerhill: A Radical Approach to Child-rearing. Penguin.

Steinberg, T. (2025) ‘Unearthing history at the Blackwell School’, e-flux Education [Preprint]. Available at: https://www.e-flux.com/education/features/638581/unearthing-history-at-the-blackwell-school (Accessed: 2 July 2025).

Tough, P. (2019) The Years that Matter Most: How College Makes Or Breaks Us. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

[1] Grammarly was used to revise this document.

[2] “I notice from your survey responses that you have students on your course(s) who you would describe as having very low levels of English. I’m keen to investigate which language tests were used by such students in order to satisfy their English language entry requirement. The tests that we accept at UAL are under constant review and it’s important to note any possible relationship between a given test and low student proficiency as seen on their course. Any English language test which does not appear to accurately assess the proficiency of students can be reviewed and removed from the UAL list of accepted tests as necessary. This process of constant review helps to ensure that all students who enrol have the language skills required to be able to cope with the demands of their course.”(Gibson, 2025)

[3] I’m a firm believer than inclusion and access interventions that are enacted at a local level by members of academic staff tend to be much more effective that general measures imposed through administrative bodies. For example, Paul Tough chapter on the impact individual teachers have on Calculus grades in US Universities (Tough, 2019)

[4] The issues faced by racialised non-native English speakers academic staff are very similar to those of students. (Garrett, 2025)

[5] There is a variety of texts overing how pedagogy and language skills have been used historically in process of racialisation In the UK, examples are exemplified in Black Feminist struggles on schooling in the late 60s and 70s (Bryan, Dadzie and Scafe, 2018; Brixton Black Women’S Group, 2023) , Summerhill School’s attempts to introduce languages of their migrants communities in their optional curriculum(Neill, 1990), as well as the pressure against Welsh and Irish language in schools until recent years. In the US, a well know example is how Spanish was used as a tool racialise students who were pressured to abandon it and were forced to repeat school years as a given.(Chicano! History of the Mexican-American Civil Rights Movement, 1996; Steinberg, 2025).